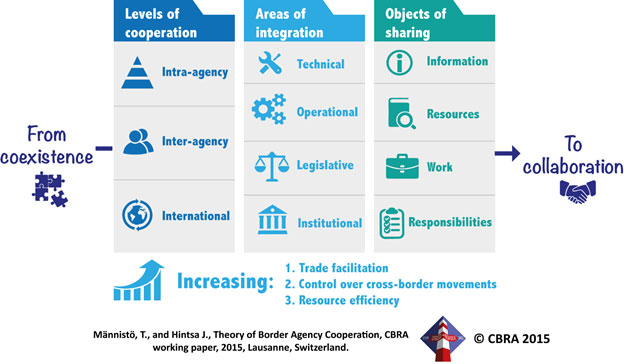

The last blog in our three-part series on Border Agency Cooperation introduces a conceptual framework capturing the essential dimensions of Border Agency Coordination: three levels of collaboration, four areas of integration and four objects for sharing. We hope that the framework helps the customs and other border agency communities to see all levels of Border Agency Cooperation (BAC) so that they can move from isolated coexistence towards more active cooperation at the borders. Higher levels of cooperation are likely to translate into higher levels of trade facilitation, control over cross-border cargo flows and resource efficiency, simultaneously. Compared with the previous BAC Blog Part 2, this BAC Blog Part 3 intends to present a comprehensive framework surrounding BAC ambitions, plans, implementations and monitoring activities – while the previous BAC Bloc 2 focused purely on a set of 15 key BAC actions, grouped according to the main beneficiary groups. This final BAC Blog has been written by Dr. Toni Männistö of CBRA.

Let’s start by first presenting the BAC diagram: Conceptual framework on Border Agency Cooperation (source: Männistö, T., and Hintsa J., 2015; inspired by Polner, 2011 and by Institute of Policy Studies, 2008)

Levels of cooperation

Intra-agency cooperation is about aligning goals and work within one organization, either horizontally between departments or vertically between headquarters and local branches, in particular border-crossing offices / stations. Ways to foster horizontal intra-agency cooperation include development of intranet networks, cross-training, inter-departmental rotation of staff, and establishment of joint task forces that tackle multifaceted challenges like transnational terrorism. Ideally, the vertical cooperation would be bi-directional: headquarters would define priorities and objectives and then communicate them to local branches. The branches would, reciprocally, send back status reports and suggest improvements to the general policies. Solving intra-agency cooperation lays a basis for broader cooperation: it’s hard for any organization to cooperate efficiently with external stakeholders if it struggles with internal problems. The logical first step in coordinated border management is therefore breaking departmental silos and building a culture of cooperation within boundaries of one organization.

Inter-agency cooperation, at the operational level, concerns relationships among a broad range of border agencies that play a role in controlling cross-border trade and travel. In many countries, primary agencies present at the borders include customs, border guards, immigration authorities and transport security agencies. However, also police organizations, health authorities, and phytosanitary and veterinary controllers, among others, take part in border management. According to a recent study, typical areas of customs- border guard inter-agency cooperation can include strategic planning, communication and information exchange, coordination of workflow of border crossing points, risk analysis, criminal investigations, joint operations, control outside border control points, mobile units, contingency/emergency, infrastructure and equipment sharing, and training and human resource management (CSD, 2011). Governmental inter-agency cooperation occurs between border control agencies and ministries and policy making bodies that are responsible for oversight and financing of border management activities.

International cooperation may take place locally at both sides of a border. One Stop Border Posts, OSBPs – border crossings managed jointly by two neighboring countries – are prime examples of such cooperation. One Stop Border Posts can involve various forms of collaboration: harmonization of documentation, shared maintenance of the infrastructure, joint or mutually recognized controls, exchange of data and information and common investments in infrastructure and so forth. Operational arrangements between the Norwegian, Finnish and Swedish customs illustrate advanced international cross-border cooperation that save time and money of border control authorities and trading companies. The cooperation builds on division of labor, where the national border authorities of each country are allowed to provide services and exercise legal powers of their home country and neighboring countries. For instance, when goods are exported from Norway, all paperwork related to both exports and imports may be attended by either Swedish, Finnish or Norwegian customs office (Norwegian Customs, 2011). At the political level, this requires international cooperation between authorities and policy makers in two or more countries. Operational cooperation (e.g., mutual recognition of controls or regional Single Window), often bringing tangible trade facilitation benefits, usually follows from political, supranational decisions (e.g., the WCO’s Revised Kyoto Convention and SAFE Framework of Standards).

Areas of integration

Technical integration often entails improving connectivity and interoperability of information and communication technology systems within and across organizations. Single Window solutions are typical outcomes of technical cooperation as they enable automatic exchange of electronic trade information among border control agencies. The UN Centre for Trade Facilitation and Electronic Business, UN/CEFACT, is an important international organization helping to build connectivity across countries and between business and governmental stakeholders. UN/CEFACT, for instance, develops and maintains globally recognized standards for EDI messages.

Operational integration is largely about coordination of inspection and auditing activities among border control agencies. Benefits of synchronized activities are evident: organizing necessary controls at one place and at the same time reduces delays and administrative burden that trading companies and travelers face at borders. A simple and powerful example of operational integration is coordination of opening hours and days of customs offices at the both sides of a border. Operational integration also covers provision of mutual administrative assistance, joint criminal investigations and prosecution, and sharing of customs intelligence and other information.

Legislative integration seeks to remove legal barriers and ambiguities that prevent border control agencies from exchanging information, sharing responsibilities or otherwise deepening their cooperation. Essentially, most forms of Border Agency Coordination require some degree of legislative harmonization and political commitment. For example, Article 8 of the WTO/TFA to the WTO Members requires that national authorities and agencies responsible for border controls and dealing with the importation, exportation and transit of goods must cooperate with one another and coordinate their activities in order to facilitate trade.

Institutional integration is about restructuring roles and responsibilities of border controls agencies. An example of a major restructuring is the annexing of US border control agencies – including the US Customs and Border Protection, Transportation Security Administration and Coast Guard – into the Department of Homeland Security, DHS, a body that took over the key governmental functions involved in the US non-military counter-terrorism efforts in the aftermaths of the September 11th, 2001, terrorist attacks.

Objects of sharing

Sharing of information – data, knowledge and intelligence – reduce duplicate work (e.g., sharing of audit findings), enable operational coordination (e.g., synchronized border controls) and facilitate development of common agenda for future border agency coordination. At the global level, the WCO’s Customs Enforcement Network CEN is an example of a trusted communication system for exchanging information and intelligence, especially seizure records, between customs officials worldwide. Another WCO initiative, the Globally Networked Customs, analyzes potential to further “rationalize, harmonize and standardize the secure and efficient exchange of information between WCO Members” (WCO 2015).

Resource sharing involves multi-agency joint investments in equipment, facilities, IT systems, databases, expertise and other common resources. The joint investment activities are likely to result in higher resource utilization and bulk purchasing discounts. For example, national and regional Single Window solutions are often outcomes of joint development and investment activities of various government agencies.

Sharing of work is mostly about rationalization of overlapping border control activities, controls and formalities. If two border control agencies, for instance, agree to recognize each other’s controls, there is no need to control the same goods more than once. Combining forces to investigate and prosecute crime also often help border control agencies to use their limited resources more efficiently.

Sharing of responsibilities is about coordinating and streamlining administrative and control tasks among border control agencies. Norway, again, sets a good example of sharing the responsibilities. The Norwegian customs represents all other border control agencies – except the veterinary office – at the frontier. Customs officers are responsible for routine border formalities, and they summon representatives of other border control agencies as and when the officers need assistance. Internationally, the Norwegian customs cooperates closely with Swedish and Finnish border control authorities at the Northern Scandinavian border posts. Bilateral agreements between its neighbors allow Norwegian customs officers authority to perform most customs checks and formalities for and on behalf of their Swedish and Finnish colleagues. The coordination decreases border-crossing times and lowers administrative costs for trading companies and the border control agencies in the three countries.

This concludes now our three-part series on Border Agency Cooperation. In Part 1, we shared an illustrative worst case example on how complex, slow and expensive a cross-border supply chain execution comes when no cooperation takes place between relevant government agencies, neither nationally nor internationally. In Part 2, we presented a conceptual BAC model with 15 key actions to improve the degree of cooperation in a given country or region – for the direct benefit of supply chain companies, or government agencies, or both. And in this Part 3, we finally presented our comprehensive BAC framework, which hopefully helps government policy makers and border agencies to design, implement and monitor their future BAC programs and initiatives in an effective and transparent manner. Toni Männistö and Juha Hintsa.

Bibliography:

Center for the Study of Democracy (CSD), 2011. “Better Management of EU Borders through Cooperation”, Study to Identify Best Practices on the Cooperation Between Border Guards and Customs Administrations Working at the External Borders of the EU.

Institute of Policy Studies 2008, Better connected services for Kiwis: a discussion document for managers and front-line staff on better joining up the horizontal and vertical, Institute of Policy Studies, Wellington, NZ.

Männistö, T., and Hintsa J., “Theory of Border Agency Cooperation”, CBRA working paper 2015, Lausanne, Switzerland.

Norwegian Customs, 2011. Case Study on Border Agency Cooperation Submitted by Norway for the November Symposium.

Polner, M. (2011). Coordinated border management: from theory to practice. World Customs Journal, 5(2), 49-61.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 2011 Border Agency Coordination”, UNCTAD Trust Fund for Trade Facilitation Negotiations Technical Note No. 14.