Mr. Tom Butterly on trade facilitation projects

CBRA Interview with Mr. Tom Butterly on global trade facilitation initiatives and projects

Hi Tom, and great that you could join a CBRA Interview. Can you please tell me a bit about yourself and your background?

Thank you Juha. Yes, I consider myself very fortunate to have had a long and rewarding career in trade facilitation and development. I am very passionate about this work. I firmly believe in the potential of trade, if approached in a just and equitable way, to create meaningful employment, reduce poverty and enhance the living conditions for citizens in a country. It is very satisfying to be involved in projects that aspire to this.

My background in trade facilitation goes back a long way. I started work in Ireland in a large telecommunications company exporting globally and then moved to Canada where I worked with the government of Nova Scotia Canada to promote international trade. From there I spent several years in Africa and then globally working in international trade development and facilitation. I believe I have actually worked in over 70 countries at this stage!

During the past 15 years I was the Deputy Director for Trade and Economic Cooperation at the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, UNECE, where I played a strong role in developing many key global trade facilitation recommendations and standards and supported the implementation of trade facilitation reform in many UN Member States. This was a great experience for me.

My most recent activity as of January this year was the establishment of Trade Development and Facilitation, TDAF Consulting ( www.tdafconsulting.com ), and I am very excited about this new venture.

You mentioned your long career in trade facilitation at UNECE – that’s where we two actually met first time, around 2003, I believe. Could you share a brief success story on UNECE’s work in this area?

Well, as I mentioned, working in the United Nations was a most fulfilling experience. It was a real lesson in the power of what can be achieved when people get together for a common cause – and I also learnt about the challenges involved in achieving global consensus!

As you know, UNECE is a major player in trade facilitation and has developed many of the global standards in this area through its UN Centre for Trade Facilitation and Electronic Business (UN/CEFACT). My most rewarding work at UNECE was related to the development of the suite of Single Widow Recommendations – UNECE Recommendations 33, 34 and 35 – and the associated work in helping countries around the world to implement Single Window facilities. You were involved in this work and I think you will agree that Single Window has emerged as a very powerful trade facilitation instrument which, if implemented properly, can result in a dramatic improvement in trade competitiveness through the associated simplification, harmonization and integration of trade process. I always emphasise that this work should not focus on the IT solution – rather, it is all about government and business working together as partners to simplify the trade processes for the benefit of everyone – and then use IT to help achieve this!

There are many other projects I was involved with that are worthy of note but I will mention just one – the UN Trade Facilitation Implementation Guide, TFIG. Again, you participated in this project and TFIG has become the most complete on line guide to trade facilitation – available in five languages and supported by all the key UN Agencies involved in trade facilitation (see tfig.unece.org ).

Now you have your own consulting company, TDAF Consulting. How do you help your customers and what kind of customers are you best able to help?

Establishing TDAF Consulting has been a great adventure. In TDAF Consulting we are taking our long experience in this work directly to countries and organizations that want to make real progress in trade facilitation. The business has gotten off to a great start and I am currently undertaking work for several UN agencies, the OECD, and large Single Window projects in Africa. It is very encouraging to see the level of demand for this type of work and also the level of ambition that countries have in moving forward to enhance their competitiveness.

TDAF is a network of leading experts in trade facilitation and we can cover all aspects of trade facilitation, including all elements in the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement. This broad level of practical experience in implementing trade facilitation on the ground, combined with our deep policy and strategic view of trade facilitation, is what gives TDAF its strength and unique position in the market. We are a very small operation so we are very selective in the projects that we undertake but this means that we really enjoy what we do and I believe we deliver a good quality product. We are just launched and I am very excited about the potential of the business.

In which trade facilitation areas – in particular WTO TFA articles – you foresee the biggest potential to produce tangible improvements in cross-border supply chains across the globe?

I think the WTO TFA marks a major step forward in implementing trade facilitation worldwide, primarily due to the enhanced political will associated with the Agreement. I have observed through my work that many developing countries are taking this Agreement very seriously and they see it as a major opportunity to launch broad initiatives to radically enhance their trade competitiveness. So it’s not about just ticking the TFA box. The Agreement is actually a baseline for deeper reform in some countries and this is very encouraging.

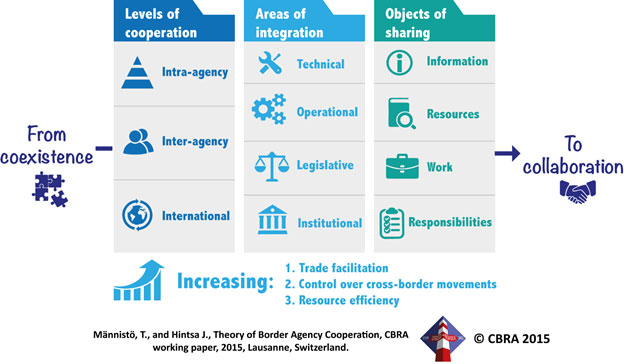

Clearly, the Agreement has many measures that greatly benefit trade facilitation. I tend to focus on issues related to the removal of regulatory and procedural barriers to trade and particularly border agency and cross border cooperation. You will not be surprised when I say that Single Window – Article 10.4 – is probably one of the most effective measures in this area as its implementation also encompasses many of the other elements of Article 10. I also think major advances can be made through implementation of Article 8 on Border Agency Cooperation and again, I see countries using these measures just as a baseline for where they want to go and what they want to achieve. From my direct experience in the field I can also say that Advance Rulings – Article 3 – is also a powerful measure from a trader’s perspective. Similarly, I think Article 5.3 has really opened up debate on the important role of test procedures and, consequently, the need for a quality infrastructure and mutual recognition thereof. It is tremendous that such debates are happening now at the political and policy level rather than just at the technical level.

The whole area of trade facilitation support structures – Article 23 – also has great potential to establish long term support for trade facilitation initiatives in developing countries and this must be strongly supported. Again I stress that I hope National Trade Facilitation Bodies see the WTO TFA as just the start of the journey that can lead to much greater participation of developing countries in the global markets.

These are very exciting times for trade facilitation!

Thank you Tom for this interview – and hopefully we can explore joint areas of interest for TDAF Consulting and CBRA, already during spring and summer 2016! See you again Friday this week in Geneva. Thanks, Juha.

Tom Butterly can be reached at tom@tdafconsulting.com